Mary Morrissy, curator of this site, takes a wander in the park and sees influences of Seurat and Kernoff in Una Watters’ The People’s Gardens (1963)

Three park views, three different painters. Una Watters painted the third of the sequence here, The People’s Gardens (oil on canvas, 40.6 x 50.8 cm) in 1963 but as a keen student of art, it seems inevitable she was familiar with the other two – Georges Seurat’s Sunday Afternoon on La Grand Jatte (1886) and Harry Kernoff‘s People’s Gardens (1945).

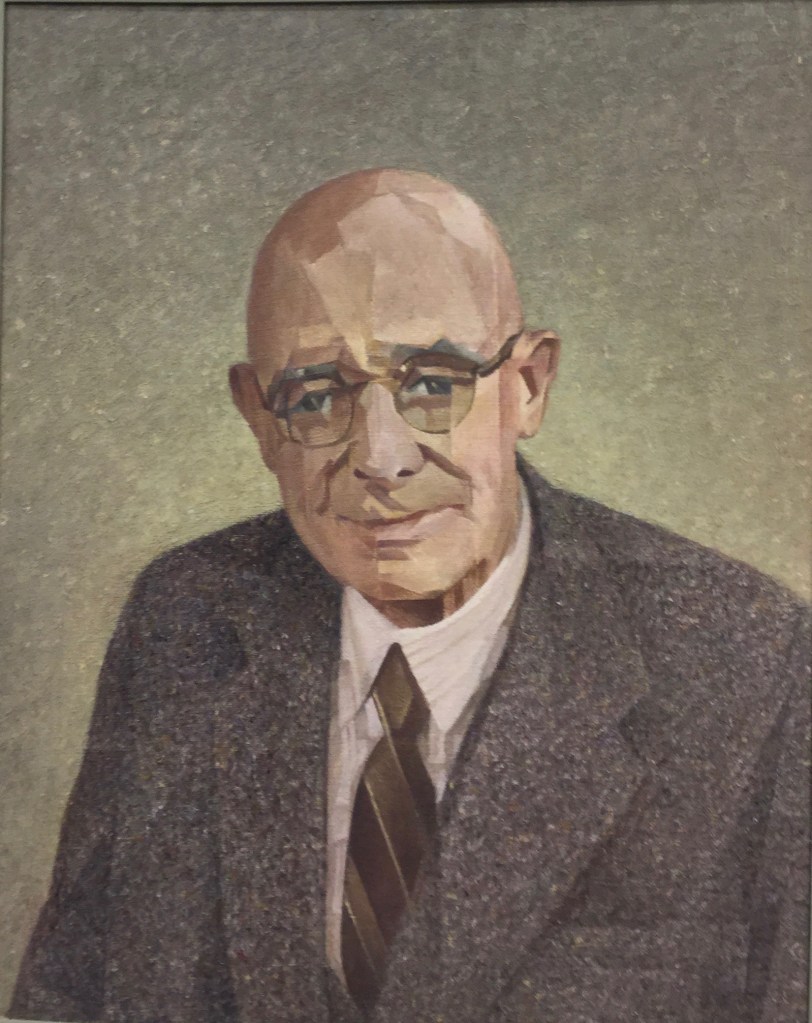

Harry Kernoff (1900-1974) was a near contemporary of Una’s and The People’s Garden, Phoenix Park Dublin (oil on board ,13.5 x 19.5 cm) was painted on the same site in 1945, nearly 20 years before Una’s. Apart from the location it’s possible to see other influences, particularly in the animation of the figures and the way the shadows are rendered. Kernoff and Una would certainly have known one another’s work through RHA exhibitions. They showed together at least once in an Oireachtas exhibition in October 1965, where Una’s Sean Tithe (see in Uncatalogued Work on this site) appeared alongside work by Kernoff and two of Una’s mentors, Maurice McGonigal and Sean O’Sullivan.

O’Sullivan was Una’s cousin, and would have been another link between her and Harry Kernoff. (It’s recorded that Kernoff painted his 1936 St Stephens’ Green, from a perch at the window of O’Sullivan’s studio at 126 St Stephen’s Green; see right.)

As well as a shared colour palette, Una’s and Kernoff’s paintings of the People’s Gardens seem similarly motivated. Here are ordinary people observed in leisure, although Una’s rendering keeps its distance and is more stylised than Kernoff’s up-close, jaunty realism. Artist Michael Kane writing in the Irish Arts Review described Kernoff as painting “the world around him as a kind of earthy, egalitarian paradise, and celebrated its gaiety and diversity with unapologetic optimism”.

That description would not be out of place when looking at Una’s urban work such as The People’s Gardens or Cappagh Road, discussed in an earlier blog on this site.

But Una’s The People’s Gardens also owes a major debt to Seurat’s 1886 pointillist masterpiece, A Sunday Afternoon on La Grande Jatte. In this work, now housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, Seurat depicted the haute-bourgeoisie of Paris, statuesque matrons with their bonnets, bustles and brollies, accompanied by their prosperous, top-hatted gents and polite children, taking the air on the fashionable side of the Seine, dressed in their Sunday best. The figures in Seurat’s painting stand, as one critic has described it, with the “solemnity of sculptures of the Parthenon”.

Compare them with the figures in Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884) on the left here – at the National Gallery London – which the painter saw as a companion piece to La Grande Jatte. He imagined the two works hanging side by side almost in a dialogue with one another. The male figures in the Bathers are working-class labourers lounging on the bank or immersing themselves in the waters of the Seine on a white hot muggy day, with the chimneys of factories smoking in the background. All of the figures are gazing towards their right – at the more fashionable side of the river where the viewer can imagine the posher denizens of La Grande Jatte are strolling. The little boy on the extreme right waist-deep in the water with the red hat could even be cat-calling at his “betters” on the other bank.

Compare them with the figures in Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884) on the left here – at the National Gallery London – which the painter saw as a companion piece to La Grande Jatte. He imagined the two works hanging side by side almost in a dialogue with one another. The male figures in the Bathers are working-class labourers lounging on the bank or immersing themselves in the waters of the Seine on a white hot muggy day, with the chimneys of factories smoking in the background. All of the figures are gazing towards their right – at the more fashionable side of the river where the viewer can imagine the posher denizens of La Grande Jatte are strolling. The little boy on the extreme right waist-deep in the water with the red hat could even be cat-calling at his “betters” on the other bank.

The democratic spirit in Una’s The People’s Gardens depicting everyday people enjoying a day of leisure at a municipal facility, are more akin to Seurat’s Bathers. But there are definite painterly echoes of La Grande Jatte in Una’s composition. Look at that sturdy little girl in yellow chasing a ball in the left foreground of Una’s painting; isn’t there an echo of the more sylph-like girl in red, skipping in the mid-ground of Seurat’s master-work? The kite-flying figure in blue in full flight in the background of Una’s work is mirrored by the man in Seurat’s mid-ground left, dressed in a rust-coloured suit with his spy glass raised. There are those pooled shadows again, and Una’s trees, with their solid angularity, have something of the same abstraction as Seurat brought to the pointillist cushions of foliage crowning his trees.

Sheila Smith, Una’s niece, has observed that Una liked to place people she knew – and sometimes herself – into her paintings. In The People’s Gardens, Sheila has identified the elderly couple on the path, one of them leaning on a walking stick, as Una’s parents.

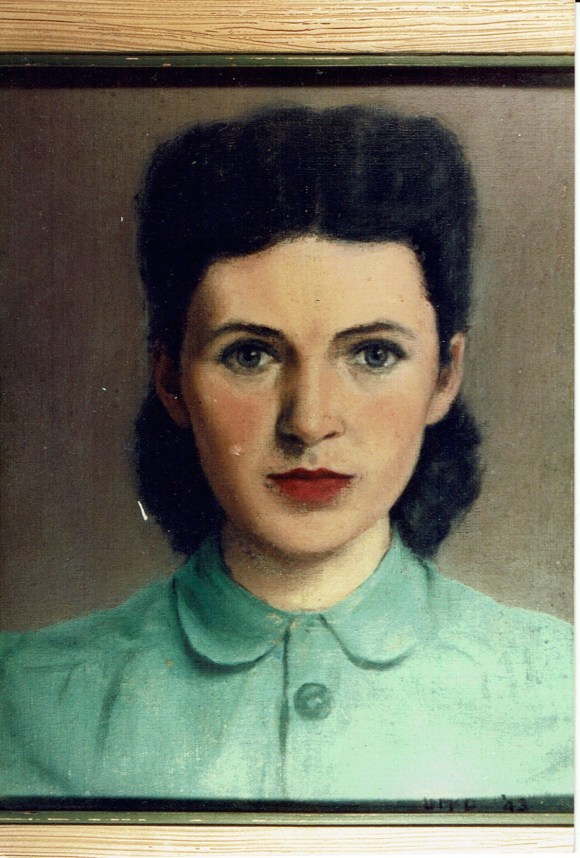

The location of both Una’s and Kernoff’s painting is an area of the Phoenix Park in Dublin originally called the Victorian People’s Flower Gardens. It was a site Una had already painted in The People’s Park, below, a watercolour from 1943 and she returned to it in 1963 with The People’s Gardens, now housed in the Hugh Lane Gallery. (Logan Sisley, acting head of collections at the Hugh Lane Gallery, has written elsewhere on this blog about the painting.)

The Gardens were initially established in 1840 as the Promenade Grounds and consist of about 22 acres. They were set up to display Victorian horticulture at its best with ornamental lakes, a children’s playground, a picnic area and formal bedding schemes. The statue that’s visible in Una’s watercolour, below, may well be the bust of executed 1916 leader Seán Heuston, a memorial in stone executed by sculptor and painter Laurence Campbell and erected in the park in 1943.

The People’s Park (1943) Una Watters; Statue of Sean Heuston (credit William Murphy); early 20th century postcard of the People’s Gardens, Phoenix Park.