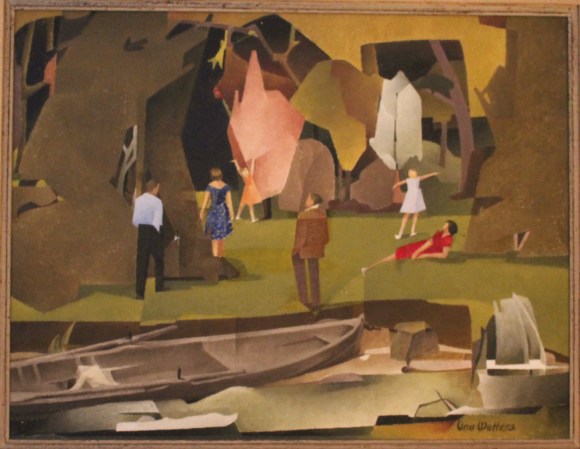

Today’s featured painting is Wild Apples completed by Una in the autumn of 1964, which records an idyllic time in the artist’s life, writes Mary Morrissy

Like much of Una’s work, Wild Apples (oil on canvas, 56 cms x 43 cms) depicts a place that was important to her – the banks of the River Suck near Ballinasloe. Una spent many summers on the river, where along with finding inspiration for her work, she did a great deal of fishing. She was, by all accounts, an expert fisherwoman, one of her many practical skills.

This is also very much a family painting. Una often placed herself in her own works and here she is the reclining figure in red in the mid-ground of the painting. Her husband, Eugene Watters – discussed in last week’s blog by Colbert Kearney – is on the left in the white shirt. His brother, Tom, is in the front foreground dressed in brown and with his back to the viewer. Tom’s wife, Bridie, and their two daughters, Georgina and Linda, complete the scene.

Georgina Donovan, Eugene’s niece, has been in touch to correct my initial mistake in wrongly identifying Eugene and Tom in the painting.

“The stances, the head shapes and indeed the clothes suggest to me that the man in brown is my father. Una used family as subjects so often in her paintings and it is just the angle of the head, the curve of a spine, a gesture caught with her brush that reminds one of the subject,” Georgina writes.

“I remember very vividly the day we discovered the crab apple tree beside the river, gathering the apples and taking them home to make crab apple jelly.”

The depiction of nature, and in particular the rendering of the trees, has much in common with The People’s Gardens discussed elsewhere on this site – see Logan Sisley, May 6. Here the angularity melds into abstraction, the trees becoming structural impressions of colour. These and the use of shadow lend a mysterious depth to the orchard or woods in the background.

The pink tree towards which the eye is drawn, hosting the wild apples of the title, is no more than a geometric block. Its sharp apex mirrors the delighted gesture of the girl in the apricot dress who has spotted the apples. We’ve spoken before about Una’s gift for expressive gesture which animates the figures in her paintings. Their faces are often not visible or are not depicted in detail, but their characters are communicated through their physical stances. We see it here again in the gambolling of the second child in the white dress – whom Georgina Donovan identifies as herself.

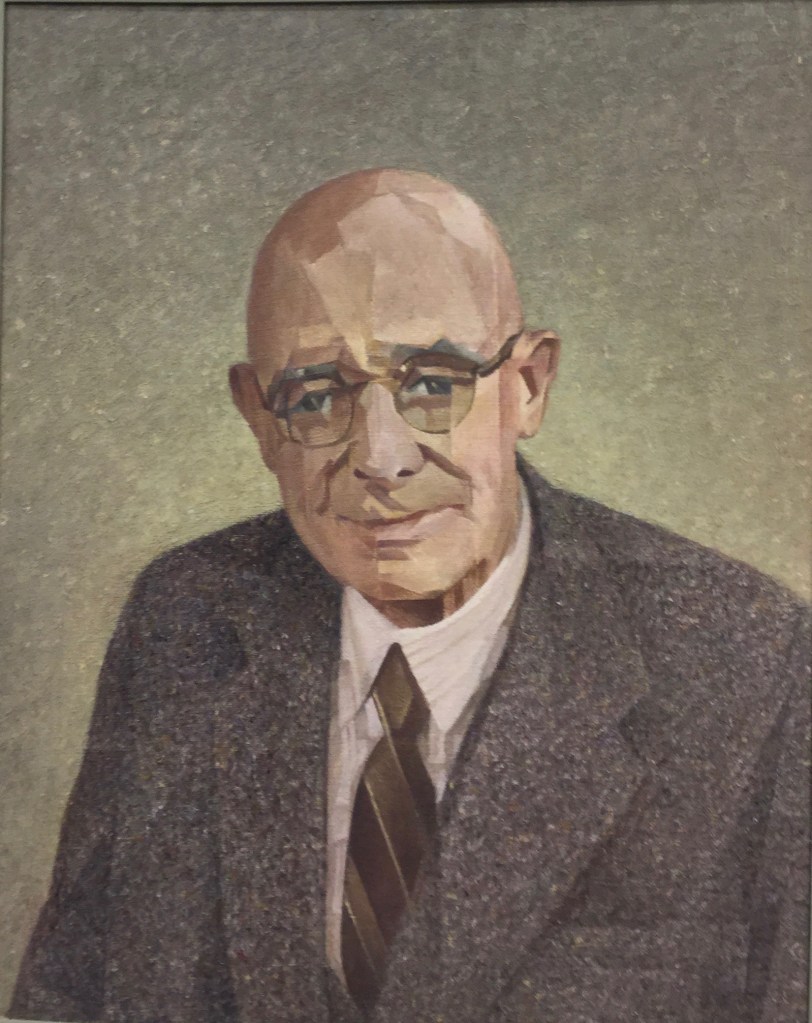

Because Eugene was a writer, we can get some notion of Una’s process from his correspondence. He was an inveterate letter-writer and he described the inspiration for this painting in a letter of October 1966, written a year after Una’s death. The idyllic symbolism of the place for both of them is clear.

“Wild Apples. . . represents any river, any landing, any discovery: but it is a real river, our Suck; an actual landing and landing place, in a grove of bog-ash and hazel in the wilderness near the mouth of the Killeglin river; and an actual discovery, the flush of crab-apples among the leaves and the delight of the children. A real moment in time and place. Moments, in fact. Our river-years. Recollected in tranquillity. And understood, by the dreaming brush, in paint.

“The colour-construct, and the grouping, convey the thematic design; a sestet of apperceptions of the apple-flush – 6 real people transmuted; the two children, the father and mother, the artist (reclining, in red), and myself . . . The boat in the picture is a real boat. Ours. But it is transmuted, the anatomy misted over in the dream of composition, till it emerges as a long thin nose pushed into the secluded creek. Base of the picture, the Archetype, in dream-grey.

“Above, the children stretch their arms in delight and desire of the wild-ripe fruit: And ye shall be as Gods. The adults, farther back, stand half-attenuated, stilled by some stir of memory, dimly aware they are on the verge of some revelation, the dress and drab riverclothes are half-transfigured, on holy ground, glimpsing the merest tinge of the quintessential red. But the real red of the picture, the Artist reclining, entranced by the remembered scene – Look! – draws the whole composition together, and (unknown to herself) forms the colour-climax and heart of the Aisling.”

Eugene’s letter also provides us with a pen picture of Una’s personality. She was, he says, very beautiful, hard-working, humorous, humble and sincere. “She knew about boats: she could pull one, patch one, cut out thwarts and knee-pieces. . . She had trained hands, could handle a trowel or an electric saw as well as a paintbrush or a pair of oars.”

This gifted pragmatism extended to, and informed, her approach to painting:

“Una never set out to paint symbols, or archetypes. These are abstract formulations, fashionable and useful terms for criticism and psychology, which had little meaning for her, and bear about the same relation to practical art-work as Theology does to the Creation. She thought sensuously, in terms of real people and common objects, actual streets and river-reaches, forms, textures, colour-tones, and transitions of light. Her sketchbooks and studies over the years reveal the wealth of observation and hard work which lies behind her wonderful last paintings.”

Una’s varied professional background – her work as a commercial illustrator and a set designer – also gave her, according to Eugene, “the discipline of abstraction and the functional aspects of design. It is all this that makes the poetry of Wild Apples possible”.

Wild Apples was sold at exhibition in late 1965. Like the Arts Council award for her winning design of the Easter Rising Jubilee symbol, the cheque from the buyer arrived after Una’s death.

Mary Morrissy