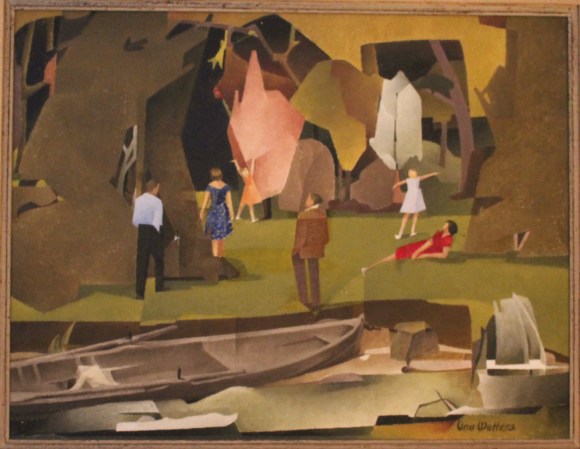

Meditation is one of Una Watters most enigmatic paintings, writes Mary Morrissy, not least because it’s undated and presents a marked departure from the social realism of her later work.

There have been many times in the course of looking at Una Watters’ work that I have wished she were still alive to ask her about aspects of individual paintings. None more so than Meditation, which seems to me her most mysterious work.

Meditation, (oil on canvas, 61 x 70cm), is clearly a late work although there’s no date on the painting. In terms of its subject matter, it’s an outlier. Unlike her cheery, social realist group portraits in city settings, this harks back to an emphasis in Una’s early work on religious subject matter.

Her first work to be exhibited publicly – in the Irish Exhibition of Living Art (IELA) exhibition in 1949 – was an Annunciation (1948). The IELA had been founded in 1943 by Sybil le Brocquy , playwright and patron of the arts, to promote modernism. It was a direct response to the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) rejection of work by her son Louis le Brocquy and of modernist work en masse. The IELA’s mission was to provide a forum where work by living Irish artists could be shown irrespective of its “academic” credentials. This suggests that although Una’s theme might have been religious, her interpretation might have been more unconventional.

However, at the moment we cannot say that for sure. Both Annunciation and Madonna of the Ash Tree (1943), two early religious paintings, featured in the 1966 posthumous exhibition organised by Una’s husband, Eugene Watters, but we have have not managed to trace either of these works.

We also know of the existence of at least one other early Biblical painting, The Flight into Egypt, which was placed by Eugene Watters’ Irish language biographer, Máirín NicEoin in a classroom in St Canice’s School, Finglas, in 1956/57, at a time when Eugene would have been teaching there. Later, it appears to have been gifted to Una’s sister, Sr Mel, a member of the Holy Faith congregation. Eugene mentions it in correspondence but due to an oversight it did not appear in the 1966 exhibition, and has since disappeared.

So we are left with Meditation. Although clearly a religious painting, it’s rendered in an intellectually abstract fashion and in a highly stylised form. The colour palette is cool – soothing blues and mossy browns. The madonna-like figure in the blue robes, viewed in profile seated on a stone throne, is fluid but sculptural. (Her face is averted so we’re not tempted to try to identify her as a “real” person.) The religious symbolism of the golden pathway of illumination – or could it be a tongue of fire? – leading through the brown portal and towards a vanishing point suggests the painter is trying to evoke a state of mind.

The only fleshy part of this “madonna” is her hands which are warm and life-like. And that brings us to the first of the conundrums in the work. How many figures are there in Meditation? There is a darker shadow-self cloaking the madonna that suggests another “presence” in the painting, and there seems to be more than one pair of those life-like hands.

The mixture of religious symbolism and secular abstraction reaches its apex in the rendering of the figure’s veil. This element of the painting comes to dominate but what exactly is it? It could be a hat with a dove grey veil swathed around it, or is it a goitred, acorn-shaped, Picasso-like eye?

The dominance of the image brings to mind the Wordsworthian “inward eye”, the thing of beauty remembered in tranquility which can only be experienced in the “bliss of solitude”.

It’s quite likely too that there is a double meaning to this inward eye – it may not simply be a spiritual vision that is being celebrated but the mystical power of the artistic imagination.

The provenance of Meditation is not entirely clear. Although a late work and an oil, it strangely, did not feature in the 1966 show. Whether it had been already been sold and/or gifted before 1966 is not known, but it disappeared from view until the early 2000s when it was purchased by Irish collector Sean O’Criadain, who acquired City Bridge (1964) at the same time – see blog of June 9. It was put up for auction again at Adams’s Dublin in 2007 where it was bought for €11,000.

When it came up for public auction, only one of two of Una’s works to do so, the Adams catalogue noted her religious sensibility and the sense of humility and quietude evident in the work. The painting “exhibits this quality, the rounded simple forms and autumnal hues creating a harmonious intimate mood”.

Elegant and restrained, Meditation does not yield up a reading easily. The mystery makes it all the more powerful.

Mary Morrissy