Una Watters had only two solo shows – one a posthumous retrospective in Dublin in 1966. But in the same year, a smaller, less heralded exhibition was mounted in Ballinasloe, Co Galway, her second artistic home.

“A brilliant artist who was just coming into her very own”[1] is how critic Patrick H Glendon described Una Watters when reviewing her posthumous retrospective exhibition held in Dublin in November 1966. It was only Una’s second solo show. The first had been held in Ballinasloe seven months earlier, when a mini-exhibition of six “historical” paintings was displayed in Cullen’s shop on Society Street to mark the jubilee of the Easter Rising.

The venue was no coincidence. Not only was Ballinasloe a home away from home for Una, where she spent many summers fishing on the River Suck in the company of her writer husband, Eugene Watters[2] (Eoghan Ó Tuairisc) and his family, but the town and environs were a constant source of artistic inspiration for her. Indeed, she could be regarded as Ballinasloe’s unofficial artist laureate.

The 1916 Rising was very much in the air in that year. As well as official commemorations to mark the 50th anniversary, writers, musicians and artists were also exploring and reviewing the seminal event – including Eugene Watters[3], whose Irish-language novel De Luain about the twelve hours leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence was published that year. But it was Una who was to play a more significant artistic role in the commemorations, though by the time the official celebrations began, tragically, she was already dead.

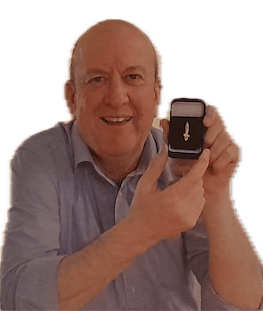

Una Watters (née McDonnell) died suddenly and prematurely at the age of 47 in November 1965, at a time when she had been at the cusp of wider national recognition for her design of the official Government-sponsored symbol for the Rising commemorations. (Indeed, the first public unveiling of a plaque featuring her design of “An Claidheamh Soluis” happened in Ballinasloe at Scoil Mhuire, in February that year.)

Una, from Finglas in Co Dublin, was already a practising artist when she met Eugene in the early 40s. Before they married in 1945 she had studied at the National College of Art. The couple lived in a cottage at Cappagh Cross, Finglas, Co Dublin, where Eugene taught in the local primary school.

It is virtually certain that Eugene handpicked the paintings for the exhibition on Society Street. A contemporary photograph of the time shows him with the six paintings gathered together in his brother’s house in Ballinasloe in April 1966. He and Una were a symbiotic couple and their artistic pursuits often merged and twinned in terms of subject matter. He was also a champion of her work, a virtue that worked against her in the end.

Although not strictly historical, Eugene’s first choice was probably sentimental. St Michael’s Church (1952, oil on canvas, dimensions not known) was the view from the Watters’ family home, “Pines View”, situated on the bank of the canal. The painting has a serene quality that was true of all of Una’s work, though she was to move on from harmonious realism into a more modernist style, inspired by elements of Cubism and Futurism.

Meditation (1951, oil on canvas, 61 x 70cms), is one such work. It is one of Una’s most enigmatic paintings, not least because it has had three different titles in its artistic lifetime. Originally, Una titled this work Old Woman (she favoured very plain descriptors) but it was sold at auction in the early 2000s as Meditation. However, in the 1966 exhibition in Ballinasloe it was called Mise Eire – possibly on Eugene’s instigation. There is evidence that he renamed several of Una’s works after her death and Mise Eire would certainly fit in better with the commemorative brief of the Ballinasloe show.

Although clearly a religious painting, it’s painted in an intellectually abstract fashion and in a highly stylised form. The madonna-like figure in the blue robes, viewed in profile seated on a stone throne, is fluid but sculptural. (Her face is averted so we’re not tempted to try to identify her as a “real” person.) The religious symbolism of the golden pathway of illumination – or could it be a tongue of fire? – leading through the brown portal and towards a vanishing point suggests the painter is trying to evoke a state of mind.

(With Mise Eire as its title, it would be tempting to reinterpret the old woman/madonna figure as Mother Ireland and the golden flame as the igniting fire of the rebellion.)

The only fleshy part of this “madonna” is her hands which are warm and life-like. And that brings us to the first of the conundrums in the work. How many figures are there in Meditation? There is a darker shadow-self cloaking the madonna that suggests another “presence” in the painting, and there seems to be more than one pair of those life-like hands.

The mixture of religious symbolism and secular abstraction reaches its apex in the rendering of the figure’s veil. This element of the painting comes to dominate but what exactly is it? It could be a hat with a dove grey veil swathed around it, or is it a goitred, acorn-shaped, Picasso-like eye, showing Una’s early flirtation with a dreamy non-realism.

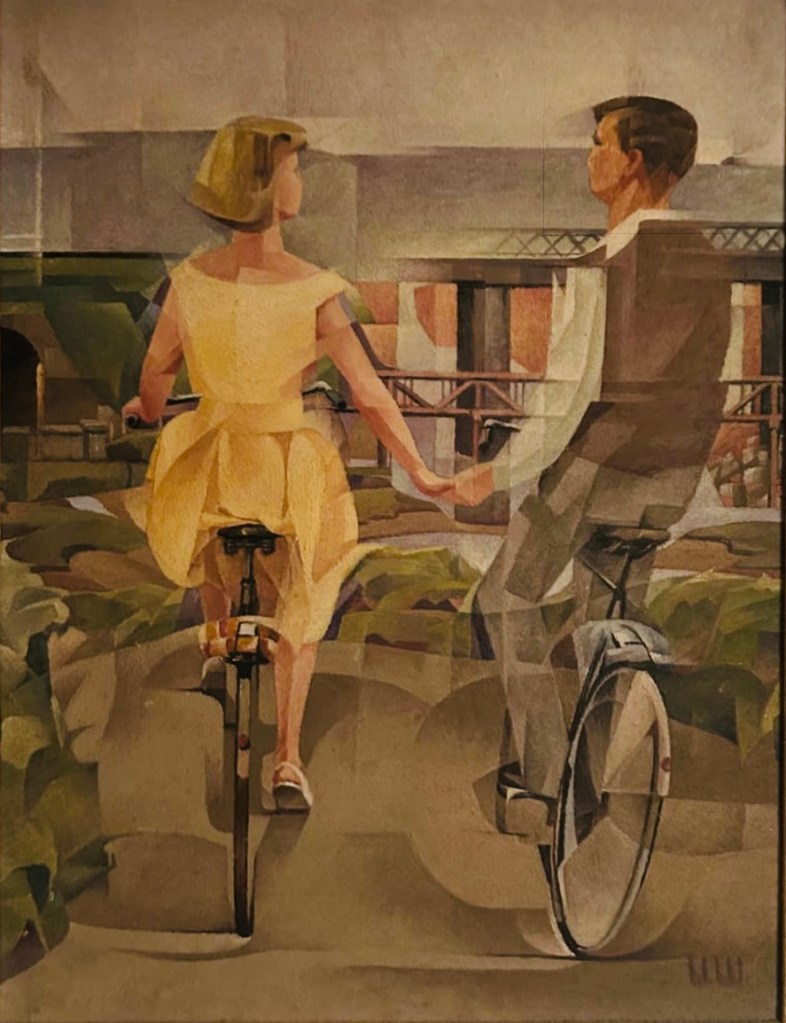

At heart, though, Una’s artistic instinct was humanistic. Her city and rural scenes of the mid-Fifties though formally experimental are almost entirely figurative. She often placed herself or members of her family in her work and she was an inveterate sketcher of friends and neighbours.

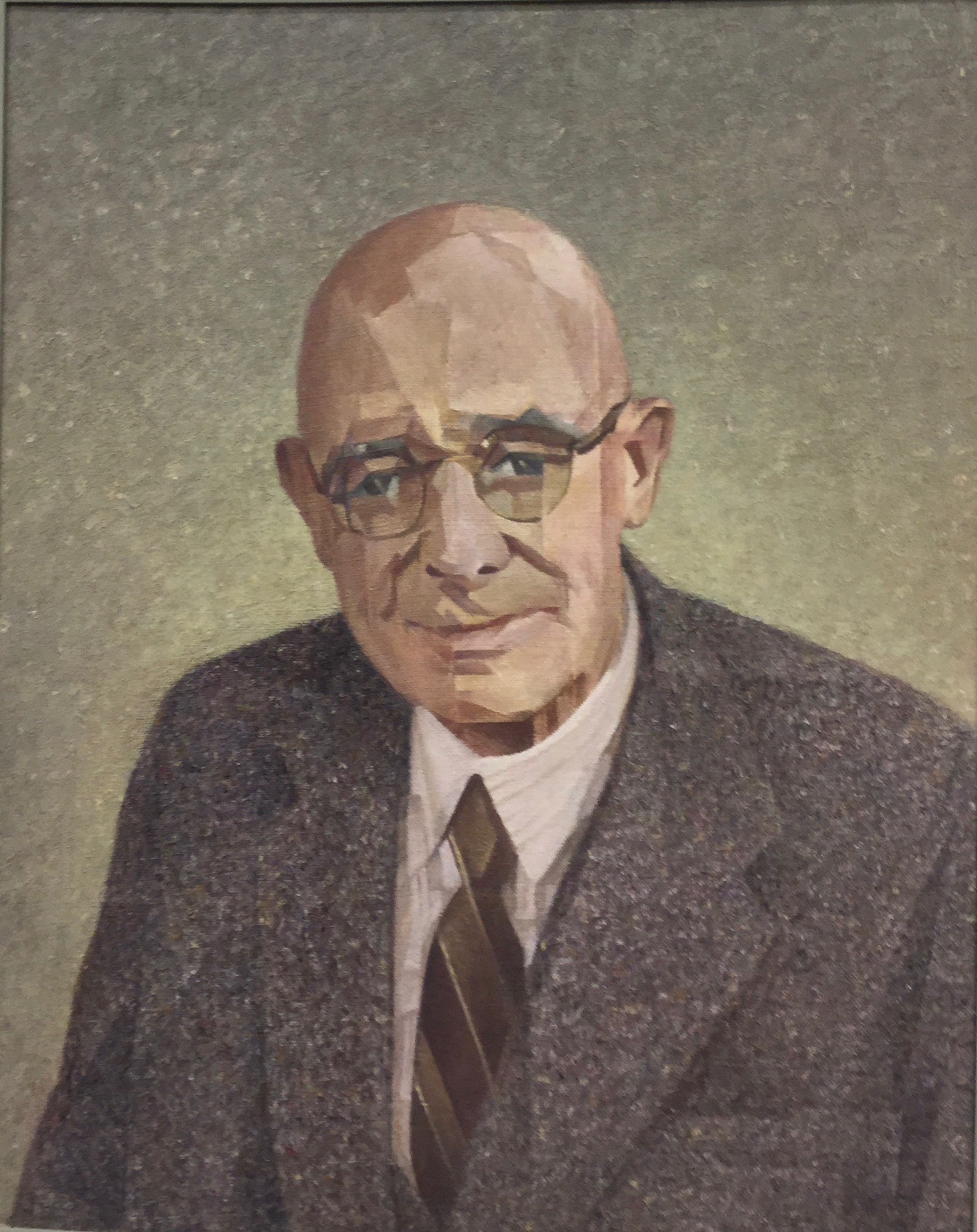

Her gift for classical portraiture is clearly on show in Portrait of Brian O’Higgins (1963, oil on canvas, dimensions unknown). O’Higgins (1882–1963) a distinguished Irish language poet, soldier and patriot, who played a leading role in the Rising, was also Una’s uncle. In 1924 he set up a publishing house which printed devotional and patriotic booklets with rallying titles such as Unconquered Ireland (1927). From the 1950s onwards the firm extended its range into Irish Christmas cards. When they needed another illustrator, Una, by now an accomplished artist was approached. As well as the Christmas cards, Una also illustrated and provided the calligraphy for a number of devotional pamphlets produced by the company.

In her depiction of O’Higgins, Una uses angular planes of light on the face and forehead to give depth and intensity to the gaze, enhancing the searching, candid look in the eye and making the sitter seem to reach out of the pictorial space. Una’s persistent interest in texture is revealed in the tufted details of his tweed jacket which looks almost tactile.

According to Una’s niece, Sheila Smith,[4] Una had been keen to paint her uncle, but she didn’t manage to do so before his death. She executed the portrait using photographs and her personal recollection of him, according to an article in the Irish Independent [5] “All who have seen it have acknowledged that the attitude is typical of the man they had known in his many moods. Certainly, in painting it, Mrs. Watters has treated her deceased subject with great sympathy and affection.”

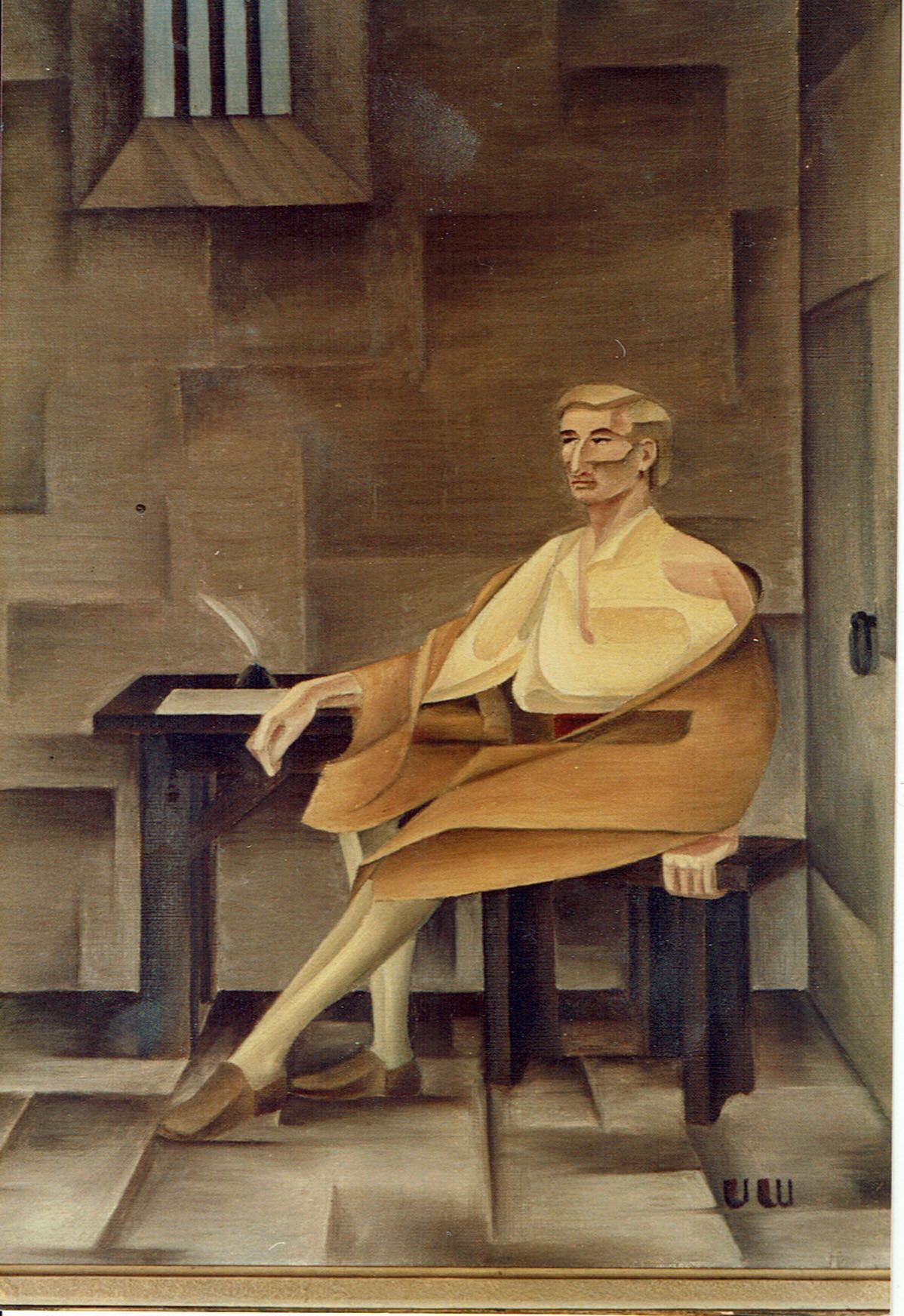

Silken Thomas in the Tower (1956, oil on canvas, dimensions unknown) is one of Una’s few historical portraits. The painting depicts the tenth Earl of Kildare, Lord Thomas FitgGerald executed by Henry VIII for leading a Geraldine rebellion against the crown in 1534. He was known as Silken Thomas because of “the gorgeous trappings of himself”[6]

After his capture the 22-year-old lord was brought to England where he spent eighteen months locked up in the Tower. Conditions swiftly deteriorated during his imprisonment. In a letter to a servant, quoted in Weston Joyce’s book, Silken Thomas asked for a loan of £20 to buy food and clothes.

In Una’s depiction, the young lord’s clothes are given due emphasis. (Una was very interested in clothes herself and was an accomplished seamstress.) He wears a camel-coloured diaphanous cloak over a cream silk shirt, a red cummerbund and a rather dainty pair of slippers. His well-tended hair and general style support his reputation as a dandy, though the gauziness of his clothes seem entirely unsuitable gear for the dank Tower of London. They reflect both his “gorgeous” trappings and the ultimate frailty of his rebellion in the face of the might of Henry VII’s monarchy.

His cell in the tower, is in comparison, heavy, solid, impenetrable. Una was fascinated with stonework – see Clonmacnoise (1958) or Girl Going by Trinity in the Rain (1959) [7]– where the textures and formations of the built world are painted with exacting brio. The figure of Silken Thomas is represented in a stoic pose, rather than examined as an individual. It begs the question whether this was a commissioned piece. The son of the owner of the painting (to whom it was gifted) told me his father, a friend of Eugene Watters, was involved in amateur dramatics and he believed the painting had been used as part of a theatre set.

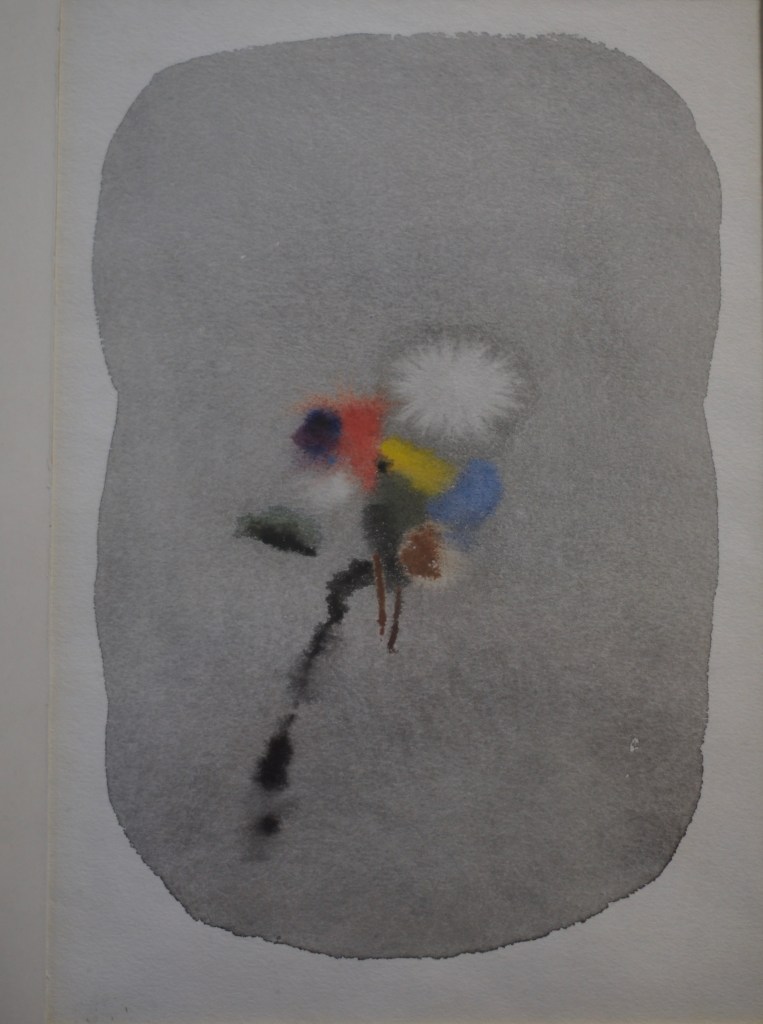

History comes wittily alive in Una’s jaunty rendition of The Four Masters (1959, oil on canvas, 60 x 70cm). It shows the authors of the Annals of the Four Masters, a seminal early manuscript written in Irish and compiled at a Franciscan friary in Co Donegal between January 22, 1632 and August 10, 1636. The manuscript is notable because the various hands which completed it were clear and legible and it was swiftly written with a pointed quill.

Una’s depiction of the four monks emphasizes this individuality. Her monastic scribes are four clearly defined personalities. The chinless younger monk in the right foreground is clearly shocking the bearded white elder on the left, who is wide-eyed and incredulous. Meanwhile, behind them, the tonsured black-haired monk on the left is in deep discussion with his older mentor – clearly, an ecumenical matter is being discussed.

Often, Una created facial expressions with broad brush strokes, relying on gesture rather than detailed rendering of physiognomy. Here, however, she departs from this practice. Perhaps she wanted to humanise these historical personages and make them seem like real people, engaged in spirited discussion? Through the apse window behind them, the outline of a blue mountain can be seen – referencing the hills of Donegal? – just like the glimpses of Italian hill towns in religious paintings of the High Renaissance.

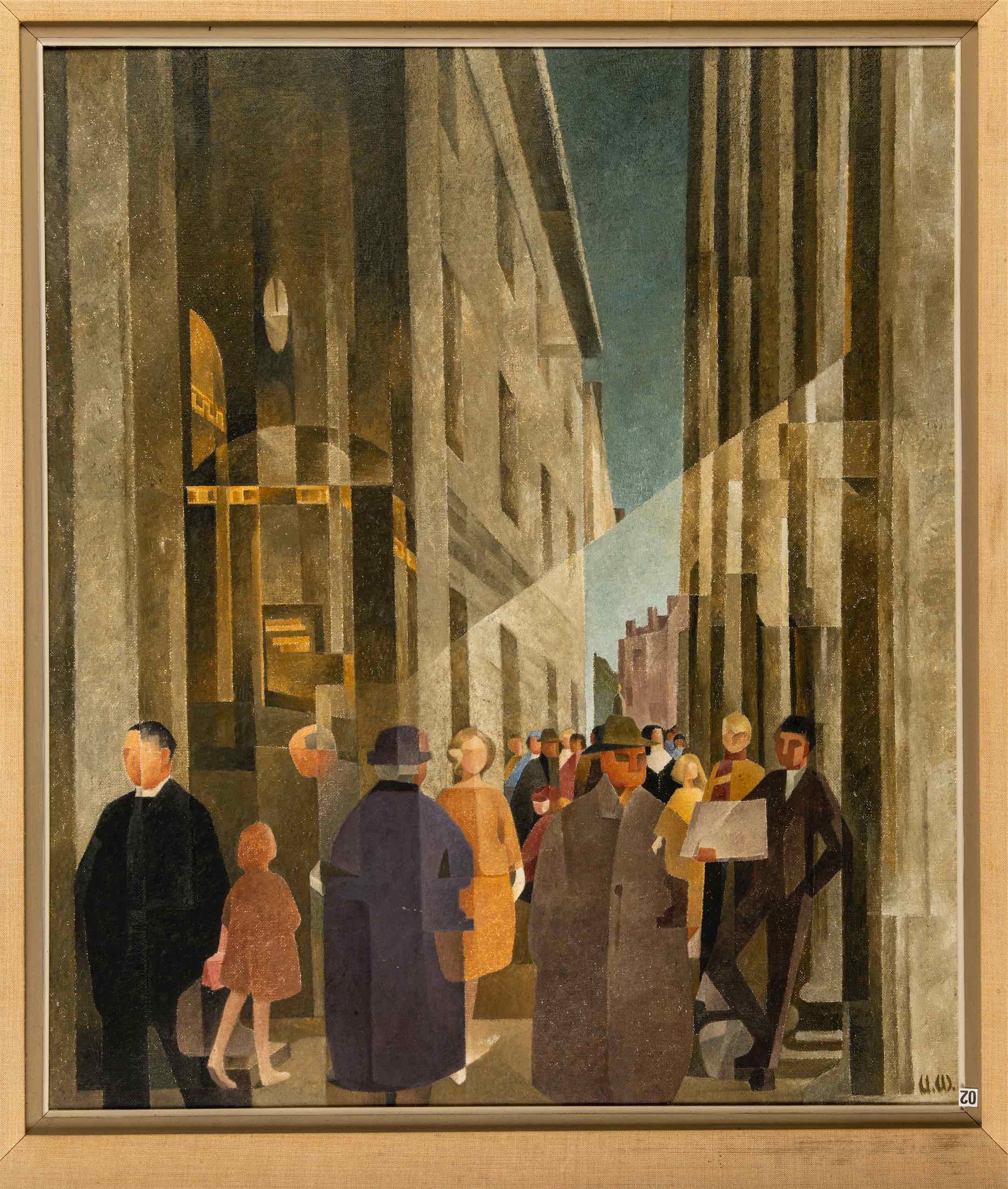

Thar an GPO (1965, oil on canvas, 75 x 85cm) was one of several Una painted in the prolific last year of her life. It was shown at the Oireachtas exhibition of that year, hence the Irish title. The painting stands out from Una’s other work in that it is political in its intent. According to her sister, Nora McDonnell, in an interview with Eugene Watters’ biographer,[8]Una saw it as a 1916 commemorative piece.

Thar an GPO is an austere work in muted earth tones and more reflective in mood than Una’s other oils. The sombre palette of the painting serves to emphasize the ray of light shining from high right to low left of the canvas. A small girl in a russet coat – thought to be a depiction of Una herself as a child – is the only figure in the painting who notices the celestial beam, which slices through the ribbed columns of Portland stone of the GPO. The light forms an illuminated pathway into which the girl steps. This motif in the work could be seen as an Annunciation of sorts – the child of the revolution (Una was born two years after the Rising) bathed in the benign light of the new republic.

As in many of Una’s group portraits, the “characters” are recognisable as archetypes, although the faces are rendered broadly and indistinctly. Here, though, they melt into one another, unified by the historic building and elevated by the revolutionary light, even if they don’t notice it. Their function is as a crowd, standing in for the many generations who have passed by the GPO.

There is some instability about the ground of the painting, given the overlapping figures so that the girl looking up at the light seems to be almost levitating. The other non-realist trope in the work is the depiction of the entrance to the GPO on the left of the painting which is suffused by a bronze light. The large entrance portal seems to open out into the pavement and we see the grey stone warmed up by an autumnal light emanating from the bronze decorative sashes on the glass. These two lights, dying bronze and transforming white, one of hope and one of defeat, seem an apt metaphorical configuration of the Rising itself.

This capsule exhibition of Una’s historical canvasses in Ballinasloe was the last but one public showing of her work for over a half a century. Later that year, Eugene organized a retrospective exhibition of 37 of her paintings in Dublin, after which rather than selling them, he distributed them and other works among family and friends.

This was a well-meaning and generous gesture but it had the most deleterious effect on Una’s artistic reputation. It meant that for over 50 years her work disappeared from view, cherished in private ownership, but not available to art historians or to be viewed in public collections or sold in auction houses. Until 2022, when I organized a retrospective of the work – Una Watters: Into the Light, at the Dublin Arts Club, along with Una’s niece, Sheila Smith – Una’s name was unknown in artistic circles. Such was her eclipse that when we were publicising her work, the most common response we got was – Who? Never heard of her!

Apart from bringing her name into the public arena, the most tangible result of the 2022 retrospective has been that Una Watters is now part of the national collection. Girl Going By Trinity in the Rain (1959) was donated to the National Gallery in Dublin as a direct result of the show.[9] The painting is on view in Room 15 and according to the gallery it has proved to be one of its most popular works. The image appears on postcards and in this year’s Gallery diary. Most satisfying, however, is that Una’s work now hangs in its rightful place, surrounded by her contemporaries – Harry Kernoff, Mary Swanzy, Mainie Jellet – whom she would have shown with in her heyday. Ballinasloe’s artist-in-residence has finally come home.

A version of this post appeared in essay form in the Ballinasloe local history magazine, Hostings, in winter 2025

[1] Irish Independent, November 25, 1966

[2] For this essay, I will use the English version of his name.

[3] Watters (1919–1982) was at that point an established bilingual author. He had written two novels in English but he is better remembered for his writing in Irish, most notably his poetry collection, Lux Aeterna (1964) and the novel L’Attaque (1962), a fictional account of the French invasion of Mayo in 1798. His reputation today probably stands on The Week-end of Dermot and Grace (1964) – a bold experiment in modernism in English described by Augustine Martin as “the most ambitious and to my mind the greatest poem by an Irishman since Patrick Kavanagh’s The Great Hunger.

[4] https://unawattersartist.com/2020/05/19/portrait-of-brian-ohiggins/

[5] Irish Independent, June 2, 1964.

[6] Patrick Weston Joyce’s A Concise History of Ireland (1910).

[7] https://unawattersartist.com/2021/08/10/unas-underworld/ https://unawattersartist.com/2021/10/21/she-stoops-to-conquer/

[8] Máirín Nic Eoin, Eoghan Ó Tuairisc: Beatha agus Saothar, (Baile Atha Cliath, An Clóchomhar, 1988)

[9] If you are interested in seeing other Una Watters work on public display – Portrait of Brian O’Higgins hangs in Navan Public Library and can be seen by appointment. The Four Masters is on display in Phibsboro Library, Dublin, and is readily accessible. The People’s Gardens is part of the Hugh Lane Gallery’s collection but is on loan to the Mansion House in Dublin.