At first sight, Una’s 1958 depiction of the sixth century monastic site Clonmacnoise (oil on canvas, dimensions not known) seems straightforward enough. It’s a partial view of this seven-acre heritage site that comprises a relict monastic city with two round towers, a cathedral and nunnery, nine churches and 700 early Christian grave slabs.

It boasts several original High Crosses, including the magnificent 10th century Cross of Scriptures (914 A.D.)

St Ciaran founded Clonmacnoise in 544 A.D. Like most monastic settlements it was established in a strategic spot on the banks of the Shannon where the river meets the Esker Ridge, a pilgrim route that ran through central Ireland.

There’s a serenity in Una’s rendering of Clonmacnoise, notwithstanding the layered and brooding sky. The buildings sweep up from the grass looking, for all the world, as if they grew there. The viewer gets less of a notion of something in ruin, as of something organic still in process. The limestone buildings are illuminated with splashes of white, perhaps lichen? It can’t be from reflected sun given the thunderous clouds overhead.

Una was interested in the physicality of stone – see Girl Going by Trinity in the Rain (1959) or Silken Thomas in the Tower (1956). Her city paintings show a materialistic exactitude about the built environment, evident in Cappagh Road (1960) or City Bridge (1965), both discussed elsewhere on this blog. But even though Clonmacnoise is a static scene, and is, unusually for Una, not animated by human figures, there is a great deal of movement and emotion in the painting.

It’s expressed in the louring sky and in the mobile rendering of the earth beneath the gravestones. It’s as if the ground is a green pool lapping up against the stone and reflecting what’s going on above the surface. Inevitably, there are dips and hollows in any graveyard where the earth subsides and where there is footfall. Una’s sensuous brushstrokes capture the surface undulations, while at the same time, creating a sense of depth, as if she’s also giving us a glimpse of an underworld that is as mobile and moody as the sky.

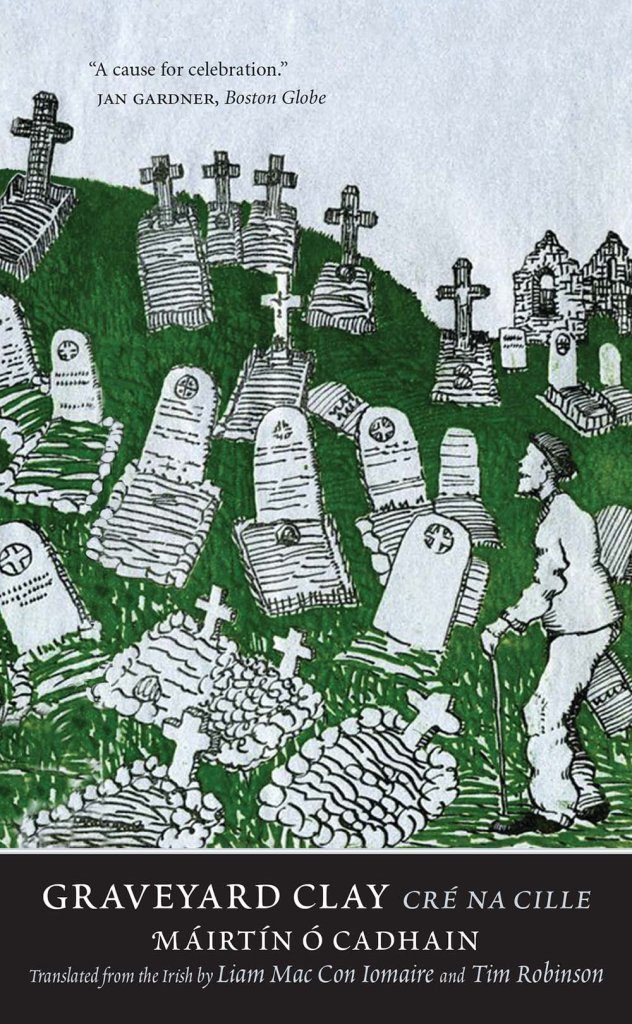

The first time I saw this painting I was reminded of Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s 1950 Irish language masterpiece, Cré na Cille. There was a copy of the novel in the bookshelves when I was growing up, and as a child, I was fascinated by the cover which shows a jumble of graveyards on a stoney hillside in Connemara. There’s no doubt that there would have been a copy of Cré na Cille in Eugene and Una’s cottage in Finglas, and that Una would have been familiar with the painter behind the cover.

Armagh-born painter Charles Lamb (1893-1964) designed the book jacket and also provided drawings of all the main characters in the story in the first edition of the novel from publishers Sairséal agus Dill.

The comic twist in the plot of Ó Cadhain’s novel is that all of the characters in Cré na Cille are dead. They are not ethereal ghosts but loud coffin-bound corpses who bitch and moan, boast and gossip about one another incessantly in a raucous chorus.

Una’s underworld may be a more dreamy and abstracted location, but like Máirtín Ó Cadhain’s graveyard, it’s very lively. Whatever it is, it’s certainly not dead. The buildings, as Una paints them, seem solid and stalwart, despite the turbulence overhead and underground. They stand as a symbol of faith – the painter’s own, perhaps, since she was a believer? – in an unstable world.

Eugene Watters described this duality as the essence of Una’s style i.e that her work had at least two meanings. “While remaining true to the mood and shape of the natural scene, it should have other suggestions built into it.”

Some of Una’s early work was of religious subject matter and there is a meditative, harmonious quality to even her most social of paintings. A year later, in 1959, she would return to monastic Ireland with The Four Masters, which hangs in Phibsborough library where she worked as a librarian before her marriage.